Aged care residents inspire with their courage, effort, and resilience

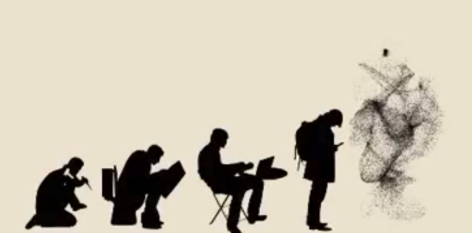

Australia has an ageing problem. Yes, our population is getting older, but this isn’t the problem. The area we need to address, is actually our view of older adults and our role in the ageing process. The words typically attributed to ageing are slow, tired, grey, fragile, unsteady, weak and even boring. Whilst most of us consider ourselves respectful of the elderly; we often veil this respect with notions of care, protection, and pity. More specifically, we make decisions or interact with older people in a way which reflects our notion of fragility, weakness and disability. Whilst well-intentioned, our efforts to prevent injury and provide help, actually results in progressively removing an older persons ability to be independent. This needs to change.

In 1948, a little known German-British neurologist Dr Ludwig Guttman faced a similar challenge. World War 2 had ended a few years earlier, and Dr Guttman was in charge of rehabilitating returned servicemen and women at Stoke Mendevill Hospital. His unique approach to rehabilitation focused on ensuring that each of his patients could become ‘useful members of society’. He empowered his patients to look beyond what they had lost, and challenged them to “make the most of what you have left. Remember, what counts is ability, not disability”.

As a way of encouraging participation in physical activity, Dr Guttman introduced sport into the rehabilitation of all of his patients. On 29 July 1948, the day of the Opening Ceremony of the London Olympics, the Stoke Mandeville Games were launched. The games consisted of 16 competitors and one event, and were shrouded in scepticism from other medical professionals. Seventy-three years on, Dr Guttman’s games have evolved into the Paralympic movement which we know today.

Interestingly, the name ‘Paralympics’ is not a reference to disability, but to the fact that the games run in parallel to the Olympics.

Every four years, we marvel at the superhuman athletes who propel wheelchairs around athletics tracks and weave across tennis courts. We watch in wonder as table tennis paddles are gripped between teeth and archery bows are clasped with toes. We admire the fearlessness of vision impaired cyclists who race around the velodrome. And we cheer as amputee athletes swim without arms and jump with prosthetic legs. Paralympians give us the belief that anything is possible.

On 24 August 2021, the first day of the Tokyo Paralympics, a competitive event for aged care residents from across Australia was launched – the Powerlympics. The team at Guide Healthcare, a leading provider of allied health services to older adults, felt that aged care residents needed a parallel games of their own. The games were designed to create a purpose, to motivate residents to exercise, to harness competitiveness and to strengthen the sense of comradery and community. Most of all, they were about having fun!

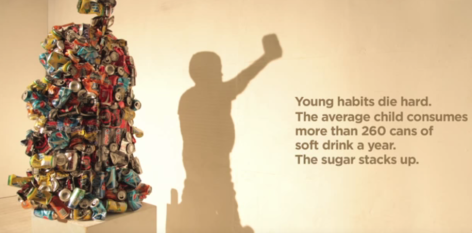

To break the ageist view of older adults, all events were ‘power-based’ —cycling, rowing, long jump, and weightlifting. That’s right, there were no bean bags, quoits or pool noodles in sight. Each event had two categories to ensure that as many residents as possible could compete.

Over the four weeks of competition, the team uncovered a 102-year-old weightlifter from Wollongong. She completed ten deadlifts of a four-kilogram kettlebell in thirty seconds. The gold medallist from the Central Coast completed 39 lifts of an eight-kilogram kettlebell.

An 82-year-old resident in Canberra launched 88 centimetres in the unassisted long jump; a resident from Goulburn jumped 150 centimetres in the parallel bars; a 79-year-old competitor from Canberra won gold in the 90-second rowing, by pulling his way to 648 metres; and in the cycling, our winner completed 300 meters in under 20 seconds!

Like the Paralympians, older adults are inspiring. Each day, they overcome incredible obstacles with humility, courage, and a smile. The seniors in our communities and our aged care homes need to be empowered to believe that they are capable of feats beyond their expectations. We need to create confidence, not fear. If we try to ‘protect’ older people, we are facilitating the process of frailty, immobility and dependence. As much as possible, our aim should be to ‘work with’ older people, not ‘for’ them. Let’s aim for strength, not safety.

The inaugural Powerolympics saw more than 300 older athletes compete for their homes. In the last week of competition, more than 50 athletes participated in live streamed events over a 5-day period. There were no complaints of pain, no injuries, and no regrets. In fact, it was quite the opposite, as aged care hallways filled with energy, laughter, and cheers. On those days, no one felt ‘old’.

Dr Guttman was quoted as saying, “If I did one good thing in my career, it was to introduce sport into the rehabilitation of disabled people.” It may just be the best thing that you can do for yourself, or for an older person you are close to as well.

pic: Victor Freitas