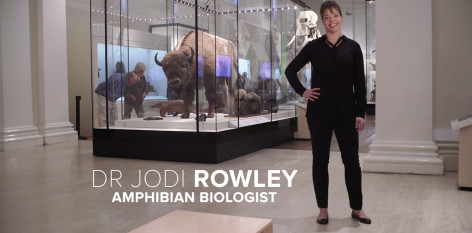

Nick Schiavuzzi considers the circumstances that led to the election of Donald Trump in light of TEDxSydney alumni Rachel Botsman’s recent TED Talk ‘We’ve stopped trusting institutions and started trusting strangers’.

Watch Rachel Botsman’s talk at TED.com

In her TED Talk from June, Rachel Botsman describes the notion of trust as elusive. Difficult to define and hard to achieve en masse, she suggests that trust is at the very heart of human interaction.

She suggests that historically, we have moved from originally instilling trust in other individuals in very local and closed settings, such as small towns and villages, through the upheaval of the industrial revolution, eventually arriving at a point where large, multinational, monolithic institutions (banks, governments, organized religions) necessarily required people to invest their trust in a brand, a name, or a set of ideals.

But Botsman suggests that there has been a ‘trust shift’ in recent history, and our willingness to trust these, now old, institutions is scant, and we are currently more open to placing that trust in others, elsewhere.

Having just endured one of the most divisive and venomous United States federal elections ever, the idea of institutional trust is one that is, at best changing, and at worse, non-existent.

The manner and tone of the seemingly interminable race to the White House between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump was beset on all sides by insults, accusations, suspicions and conspiracy theories. Very light on policy detail and more a contest of personalities and personal proclivities, this past election season has had the dark arts of politics possibly put the final nail in the coffin of any remaining public confidence in the political establishment and its processes.

In the face of this year’s US election saga, and the tactics that dominated it, we are trusting strangers that exist outside these institutions more and more. Operating outside the bounds of traditional institutional paradigms, Botsman sites the rise of interpersonal and community-based digital apps – think Uber, AirBnB – as evidence of our renewed tendency to place trust in individuals that exist outside these old institutions and exist on a more equal and personal level.

Perhaps more than any other beast, politicians have trust as their primary currency. It is at the heart of their existence. It is hard-won, difficult to judge, and easily lost.

However, and crucially for politicians, Botsman notes quite poignantly that the dynamics of trust generally have changed. No longer is trust top-down and opaque. No longer is it faceless and distant. But it is now inclusive, transparent and immediate. And the more we trust in a direct way with each other each day, the more immediate the notion of trust will become.

There are some key parallels here with the Clinton-Trump race. It was a race of – quite literally – ‘he said, she said’. More generally, though, it was framed as a contest between Clinton’s political establishment resumé and experience, and Trump’s rogue outsider, everyman show that preyed on latent frustrations and fears already existing in the community, be they real or imagined.

Trump’s campaign, especially, drew its life force from much of that frustration being directed at the political establishment, and his assurance that he existed aside from it and aimed to break that framework down.

It was the old, opaque, secretive institution up against a new, boisterous immediacy.

To use Botsman’s model and terminology, how significant has our ‘trust shift’ away from institutions been? How much of Donald Trump’s victory can be attributed to the bottom finally completely falling out of our inherent historical trust in the idea of government and the political system?

Rather than a victory aimed at ‘Making America Great Again’, is President-elect Trump, ironically, a defeat for the very idea of institutional government itself.

Donald Trump was not the only figure in this year’s presidential race to have success playing to the simmering displeasure aimed at the political establishment. On the other end of the political spectrum, Bernie Sanders’ grassroots campaign that targeted ‘The 1%’ struck a chord with a youth vote that Hillary Clinton has historically struggled to court.

Common to both the Trump and Sanders campaigns has been the idea that the candidates have purported to exist ‘outside the system’. They have sold their fortunes as those of men operating in the recesses of political elitism and speaking ‘for the ordinary people.’

Traditionally, and in keeping with Botsman’s historical map of trust and institutions, Presidential candidates have been at pains to convince voters of the knowledge and experience they have garnered from years inside that same political system. Why? Because the conventional thinking was that if they could sell that idea more effectively than their opponent, the electorate would trust them. And then elect them.

But this year, such was the distrust towards government and party politics in America, the mere idea of an outsider saw two unheralded campaigns gain ferocious momentum. One looked, for a time, as though it might pinch the Democratic nomination. The other has ridden that momentum, allowed it to take on a life of its own, and has now used it to gatecrash the Oval Office.

Sanders railing against the inequitable distribution of wealth in the US and Trump portraying all and sundry as corrupt and bowing to vested interests have been utterly captivating messages. The veracity of these claims, whichever side of the political aisle you may fall, is somewhat beside the point.

The point here is very much that the idea of an ‘outsider’ has proven to be a decidedly energizing one for many voters and one they feel more connected to. Because at the end of the day, the electorate itself paradoxically exists outside the political system.

In short, people are seemingly keen to trust these supposed outsiders and renegades, often simply because they say they are outsiders and renegades and offer up a steady diet of common ground via sound bites. This support and trust on the part of the electorate are perhaps less a considered acknowledgment of the virtues of these campaigns and their messages, and more of a manifestation of the lack of trust for the political system Sanders and Trump have sought to rail against.

These forces and tendencies seem to hold genuine similarities to the phenomena Botsman describes in our ‘trust shift’. More willing to trust transparent individuals rather than opaque institutions, the mirage of a major political candidate that claims to ‘tell it like it is’ and sells their story as a single voice amidst a choir of political conformity is an intoxicating idea indeed.

The question now is, given the successes of Trump and Sanders this year, have we now found a new political playing field where these types of candidates will become commonplace? This leads to the consideration; has our new found willingness to trust strangers in the ways Botsman notes – on a technological and interpersonal level – emboldened us to apply the same logic to larger, more telling questions around government, policy, and representation?

We could well be on the verge of an age of the populist political outsider.

As always, though, there is another side to this coin. As much as a ‘trust shift’ may have emboldened the American electorate to embrace these so-called outsiders, it can also be seen as a rejection of over two hundred years of America’s almost religious adherence to that idea of The United States Government.

Hillary Clinton entered the presidential race as a former Senator, former Secretary of State, former corporate lawyer, former healthcare reformer, former First Lady and as the potential first female President ever.

Objectively, and as President Obama himself noted at the Democratic Convention, she was the “most qualified candidate ever” to run for the Presidency.

Despite all this, and despite the fact her ultimate opponent was Donald Trump – easily the least qualified and suitable candidate ever – Clinton was still unable to galvanize enough of the electorate using the old model of institutional stability and experience to take her place in the big chair on Pennsylvania Avenue. The fact that this election was even a contest, let alone the fact Clinton didn’t win it, is staggering. Granted, the failing of her campaigns were many and varied, but at its core, the vote against her speaks to what she represents to people, rather than to what she is as an individual.

In the same way that Trump benefited from the lack of trust in the institution of government, Clinton’s campaign was constantly dealing with the perception that she was a part of creating what that institution had become.

Born of repeated failures of governments to be seen to be working in the interests of the ‘ordinary’ people, Botsman quite clearly says that as a part of our ongoing ‘trust shift’, we now trust individuals, transparency, and accountability. We shun or are suspicious of opaque power structures, and instilling trust in a top-down format.

Put bluntly, Hillary Clinton represents this old, opaque model. Between the forever returning questions around her use of a private email server, her conduct in the matter of the Benghazi attack, and the revelation that she has repeatedly been paid hundreds of thousands of dollars by the same Wall Street bankers she has vowed to regulate against, the central challenge to the Clinton campaign, from its very start, has been overcoming a deep sense of distrust amongst Americans.

The fact that money – in the case of the Wall Street speaking engagement fees – was part of this lexicon fed into the idea that she existed apart from those whose vote she was seeking. Part of what Botsman says about the new ‘trust shift’ is that we seek to place trust in those we have a common interest with. Airbnb guests and hosts both get rated, and on balance, are held similarly accountable.

But for factory workers hit hard by the financial crisis through Middle America, Donald Trump’s outsider story and self-proclaimed self-made image played strongly against Hillary’s ‘big end of town’ loyalties. And for university students suffocating under the weight of crushing student debt, Bernie Sanders’ promise of free tertiary education struck them as fair and just.

Add to this, Clinton’s penchant for secrecy and the perception of it exacerbated by the ongoing email scandals, and it becomes very much apparent that Clinton’s campaign challenges were rooted in her inability to extricate herself from the idea that she was the personification of the old institutional system against which Trump promised to work.

As any political story, the Clinton-Trump race essentially boiled down to a question of trust. If we view it through the prism provided by Botsman and accept that the way in which we trust others has indeed shifted, then there is perhaps no surprise that this election was fought along such sensitive and fundamental fault lines. Botsman’s original notion that trust is elusive remains.

However, in the shadows of the bitterness that characterized this election, the idea that perhaps the political battle lines for future elections have been redrawn is an important one. If trust is indeed now more inclusive, transparent and community-based, it stands to reason that politicians – as the most servile dependents in the economy of trust – will need to reassess how they engage with the electorate. Because, it very much appears that the electorate has reset the rules on how we engage with potential political leaders.

Image: #clinton as #trump – part of #trump as #selfie body of art experimentation by Oli Goldsmith – November 2016.