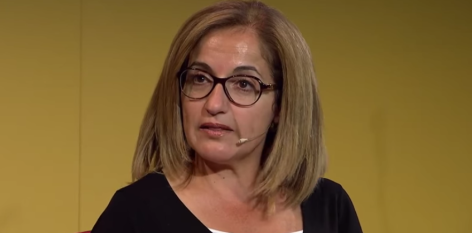

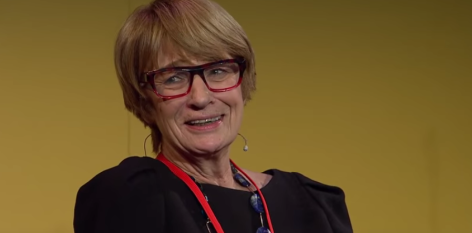

“This is the story of John and Mary, a typical Australian couple, and how gendered economic inequality plays out over a lifetime. John ends up comfortably wealthy Mary lives the last years of her life perilously close to homelessness,” writes Jane Gilmore in her introduction to The Cost of Womanhood, deftly using metaphor to answer the question you and I are asking right now: Why is that?

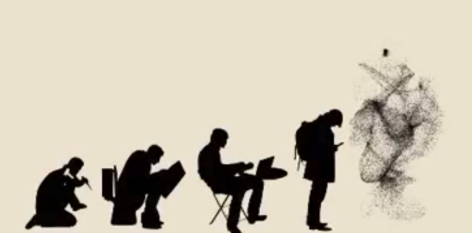

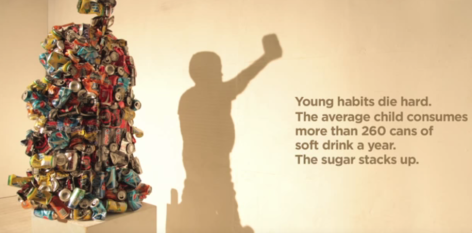

“It all comes down to conscious and subconscious perceptions of gender roles,” explains Gilmore. “Childcare is expected to be entirely done by women, not men. Women leaving the workforce, because of having children; women not getting back into the workforce, because of having children; and, when she finally does, she’s five years behind.” Opening our eyes to the real issue, she explains, “we need to look at the lifetime accumulative effect, at the long-term disadvantage.”

Gilmore questions the tacit cultural acceptance that women simply live poorer lives, and, if it’s possible to be more discriminatory, the idea that, perhaps, they have not done enough to change their financial circumstances – thus deserving their fate.

Individual men are not under attack here, to make an often misunderstood distinction, many of whom are, of course, committed hands-on parents. Indeed Gilmore’s short definition of feminism puts the “liberation of the things that keeps both men and women in positions that are bad for them” front and center.

The journalistic responsibility is impressive. “Identifying what we’re doing right and what we’re not doing right is how we get the public discussion going,” Gilmore says. “Good journalism is how we do that.”

On the subject of male violence, she’s equally erudite, flagging the assumption that women are somehow responsible: “It’s seen as a women’s issue, but they’re not the ones committing the violence. We have to start talking about what’s happening to men and boys, that they grow up being violent.”

In the Sydney Morning Herald, on the recent rash of high-profile rape cases, such as the Brock Turner trial, Gilmore makes a gutsy challenge to ’reasonable belief’ in consent. In tackling the idea that “real rape” only happens to “an innocent young girl, who is conservatively dressed, sober, suffering no mental or physical disabilities,“ she identifies the lack of validity given to the account of the female victim, particularly when drugs, alcohol and sexy outfits are involved. Making the point, as a result, that greater weight is being given to the testimony of a man accused of rape.

Male violence is the subject of her first book, Fixedit, expected to be published next year. In a few words, “it’s about the way media reports on men’s violence against women and how it needs to change,” she says.

Drawing on precise data research, Gilmore keeps her focus on the unpopular issues of male violence and women’s poverty. “The male-dominated media isn’t interested in reporting a great deal on female disadvantage” but, as she says, “it’s the job of journalists to tell people what they don’t know.”

“There’s a reason we keep sharing Jane Gilmore’s work: it’s amazing,” writes Clementine Ford. You can read it in The Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian, The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, The Age, The Daily Telegraph, and Queen Victoria Women’s Centre.

Photo by Emily Kay / The Citizen

Book now to see Jane Gilmore at TEDxSydney on Friday 16 June 2017.