Sarah Smythe explores the growing movement of ethical fashion.

Ever tried separating the clothes in your wardrobe that are polluting the planet from those that aren’t? I did and had no idea (though after my research I suspect them all). Why? Becuase the chain of supply, linking every part of the manufacturing process, isn’t fully transparent.

It’s a complicated path from raw materials to fashion ready textiles. Globalism has removed us, almost completely, from the manufacturing process and we are desensitised to the environmental cost, as a result. With many companies not knowing what happens at every link of their supply chains, the time has come time to ask: How are our clothes being made?

What we know

Fashion isn’t sustainable. “The apparel industry accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions and remains the second largest industrial polluter, second only to oil,” explains Forbes.

Supply chain research shows the use of natural fibers, like cotton and wool, have a high environmental impact, requiring large amounts of water and pesticides. Synthetic fibers also come from non-renewable resources, using considerable energy to become fashion ready textiles. Then there is the ecological cost of transportation to distribute products from low-labour-cost nations to consumer markets around the world.

The pollution combines with worker exploitation. In their 2016 Fashion Report, The Truth Behind the Barcode, Baptist World Aid Australia highlighted supply chain transparency as essential to policing enforced and child labour.

Action groups, from Greenpeace to Fashion Revolution, have brought unethical fashion practices to the public’s attention. But is it enough to detox the industry?

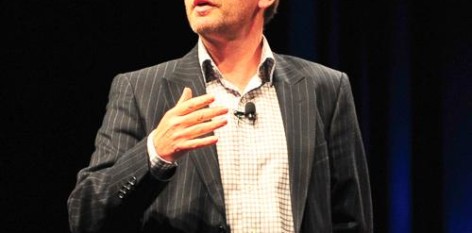

TEDxSydney, with its long-standing commitment to sustainability, featured Clara Vuletich in its 2016 year’s speaker lineup. An ecologically focused researcher and designer, Vuletich trains designers in another TED (Textiles Environment Design), a sustainable methodology, for companies like Swedish giant H&M.

Vuletich is not alone as the rag trade’s growing ethical movement testifies. But fashion has long used its canvas to challenge convention, from the 1980s Japanese designer revolution of the Paris system to Vivienne Westwood’s contemporary work on climate revolution; now it’s ready to overhaul its manufacturing methods. Greenpeace’s Detox Catwalk lists the companies – Inditex, Benetton, H&M, Valentino, Burberry, Mango, Miroglio, M & S, C & A, G-Star, Levis, Adidas, Puma, Primark and Fast Retailing – committed to the clean up.

Impressive, but as Greenpeace vigilance suggests, we have a long way to go. Moreover, a closer look shows consumer complicity – for while forward thinking companies are producing sustainable collections, market research indicates we’re not buying them. Certainly nowhere near enough for the industry to switch from a fast to a slow business model.

I Shop Therefore I Am

Fast economic models are based on ever-increasing sales. To this end, branding aligns our well-being with the product, while sophisticated marketing imbues the purchase with a quick identity fix. It’s normal to buy a T-shirt or pair of jeans, barely wear it, and throw it away in favour of a new item and a boosted sense of self.

Media scholar Stuart Ewen coined the term ‘commodity self’ to describe the identification crutch our purchases provide: My snazzy Lorna Jane tights define my ‘sexy fit self’, my elegant Rag and Bone outfit reinforces my ‘smart feminine self’, my new Tom Ford suit my ‘successful masculine self’.

This isn’t just loving a thing, it’s a fetish – a phenomenon Karl Marx, in his theory of political economy, termed commodity fetishism. Such a fantastical experience empties the product of its toxic chain of supply, replacing it with personal glamour, cultural belonging, and social success, and relieves us of any responsibility for the sacrifice of labour and environmental resources.

Toward a new aesthetic

It would seem that saving the planet and upholding human rights are currently not reasons enough to change our purchasing behaviour. Gordon Renouf, CEO and Founder of the Good On You app, explains why:

“Ethical fashion, as opposed to just clothing, must have the right proportion of aesthetics, quality, and price to sell well enough to influence the next production run.”In this way, ‘sustainability’ is viewed as value added rather than an environmental imperative.

Sounds bad, I know, but there is hope. The global fashion aesthetic is developing to include sustainability.

Vintage, second-hand and clothes swap shopping are increasingly commonplace. How many of us know the thrill of a thrift shop or garage sale purchase? Used clothes options are original. They’re more varied than the racks of market driven sameness that is so often the mainstream retail offering, encapsulating aesthetics, quality and price in a fulfilling and environmentally sound way.

The growing breed of sustainability designers has a wide range of stunning answers to our next event. 21st-century startups, like Stella McCartney before them, are seizing the opportunity to begin on a slow business model, without sacrificing fashion’s enduring aesthetic.

Emma Watson enunciated the new aesthetic when she said, “luxury to me means peace of mind,” in a CNN Style interview on her 2016 MET Gala gown. Watson, who has made a commitment to sustainability, wore a stunning Calvin Klein creation made from 100% recycled plastic bottles.

Apps, like Good On You, allow informed choices by offering instant sustainable options, including those companies that offer manufacturing transparency, enabling us to integrate ethical shopping into our way of life.

The fashion industry won’t replace a fast with a slow business model unless the consumer demands it. But if we change the industry will, eventually replacing the unethical with an ethical aesthetic in the ways necessary for economic, as well as environmental, sustainability.

We begin by going to our wardrobes with open eyes.

Original artwork for TEDxSydney by Michelle Bae