Ahead of Dr Ken Hillman’s talk at TEDxSydney 2016, Sarah Smythe reflects on the passing of David Bowie and the art of dying well.

David Bowie died as he lived, artistically. In his final days he completed and released the album Blackstar, did a photoshoot (in which he looked stunning in a Thom Browne suit), and passed away, as David Jones, at his Catskills home surrounded by nature and his beloved family. It was intensely private, which was the only way for the mature star. Bowie died well setting the style for death as he had popular music.

What is it to die well?

Blackstar would seem, apart from great music, a vehicle for acceptance, the final stage of Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s well known five stages of death. The album and the Lazarus video make meaning of life’s end, which like all good art speaks to the beholder as well as the artist.

Dr Mark Taulbert brought our attention to Bowie’s conscious approach to death. In a public letter, to the star, on a palliative care blog, he spoke of a patient facing the end of her life:

“Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation.”

“Many people I talk to as part of my job think death predominantly happens in hospitals, in very clinical settings, but I presume you chose home, and planned this in some detail.” he wrote.

Dr Ken Hillman, Professor of Intensive Care at University of NSW (UNSW) and TEDXSydney 2016 speaker, recalls his grandfather dying at home, which due to the policy of modern medicine is no longer common practice.

“The role of emergency rooms is to resuscitate and save lives, and package the patient for admission to hospital, whether active treatment is appropriate or not,” wrote Hillman in a 2009 Sydney Morning Herald article.

Hillman along with Dr Magnolia Cardona-Morrell led the UNSW research into CriSTAL (Criteria for Screening and Triaging to Appropriate aLternative care), a test to identify patients who are likely to die within a three-month period.

CriSTAL’s in depth process gives the patient every opportunity, like Bowie and Hillman’s grandfather, to spend their final time at home.

Sogyal Rinpoche, writer of the now classic Tibetan Book of Living and Dying also advocates for dying well, at home. It isn’t always possible, but it’s where people, surrounded by family and friends, feel the most comfortable.

The Eastern belief in reincarnation, karma and the bardo views dying well as a natural part of living well. But the perennial philosophy and discipline required of meditation, tonglen (giving and receiving) and phowa (conscious dying) practices, are not for everyone. Higher powers are unique to the individual – for some it is God, others nature, some stoic rationalism.

We might need to dig deeper into our cultural history for answers. Ralph Waldo Emerson said,

“Death Comes to all, but great achievements build a monument, which shall endure until the Sun grows old.”

Westerners are doers. Raising a family, guiding their development and increasing their financial security, where possible, is a monumental achievement. Legacies come in different forms: Artists, intellectuals and inventors leave bodies of work, entrepreneurs economic structures, activists and charity volunteers relieve suffering.

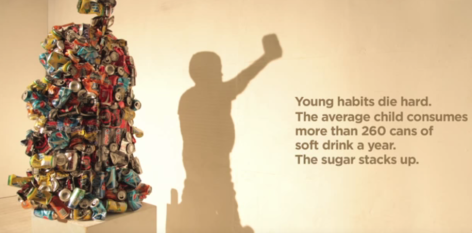

The aids quilt is a community legacy. Conceived in 1987, the 48,000 individual 3-by-6-foot memorial panel commemorates those who died from AIDS and the extraordinary activism that led to the advanced treatment we have today.

In this way a creative project becomes a practice for dying well.

Thinking something is not always enough, as our mind/body split testifies with widespread examples, from racism to sexism to homophobia to ageism to the effects of global warming. Practices are needed to integrate our intentions with our actions.

Eastern and Western approaches combine effectively to this end.

Lou Reed died in the presence of nature, doing tai chi. Laurie Anderson, his wife and avant-garde musician wrote a Farewell to the Walk on the Wild Side artist, where she spoke of his passing with acceptance, his eyes open.

“I am so proud of the way he lived and died, of his incredible power and grace,” she wrote, speaking of his creative contribution and his disciplined meditation practice in the Rolling Stone published piece.

Reed, like Bowie, died well. His Western musical legacy and Eastern meditation practice united in a divine willingness to let go.

The readiness to let go is clearly served by a legacy project, like family, art, music or community and mindfulness practices, such as meditation, tai chi or yoga. So too being in charge, where possible, of our own passing by supporting efforts like CriSTAL.

I don’t know about you, but I’m thinking of the deaths I’ve experienced – how the grace, dignity and courage contributed mightily to the lives well lived. Their stories exemplify the art of dying, which is in essence the art of living.

Photo: Brighton Sand Sculptures Glimmertwin David Bowie Graffiti by Martin Stitcher via Flickr Creative Commons.