As we delve into our first investigation of how ideas spread (see the series intro here), we discover there’s one thing that most researchers seem to agree on – the importance of social networks. Let’s uncover what this means by stepping behind the lens of a social scientist and exploring five prevalent theories.

When it comes to social networks, researchers are exploring how the intricate web of our relationships – with friends, family members, and colleagues (and their connections), both in the “real world” and increasingly online – acts as a vehicle for the spread of ideas.

The study of ideas flowing through social networks is nothing new, and social scientists have been measuring the popularity of ideas for decades. But thanks to emerging technologies, they are now tracking how ideas actually spread from person to person on a large scale and with greater precision. They are developing computer simulations of human behaviour, mapping the diffusion of content in social media, and even using digital devices to record human interactions.

While these tools are generating fascinating data and sparking new theories, the ongoing debates among social scientists suggest we still have a way to go. There is always more to learn.

Here are five theories from researchers that piece together how ideas spread through social networks:

1. The power of network structures

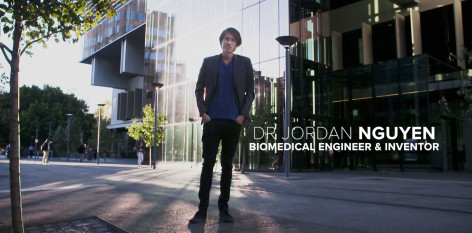

Known as the “grandfather of wearable technology”, computer scientist Alex “Sandy” Pentland (see his TEDx talk here) uses digital devices to examine the properties and patterns of interactions between people in a field he calls “social physics”.

In his book Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread – The Lessons From a New Science, Pentland concludes that the structure of our interpersonal connections rather than the content we exchange determines the quality of “idea flow”. He claims that some networks – those where group members have many interactions with highly diverse people outside of the group and where the members are also highly connected to one another – are more conducive than others to the development of new ideas.

In one study where Pentland tagged online day traders, for example, he found that the traders who interacted with a broader information network outperformed those who worked in isolation or who operated within informational “echo chambers”.

2. Location, location, location

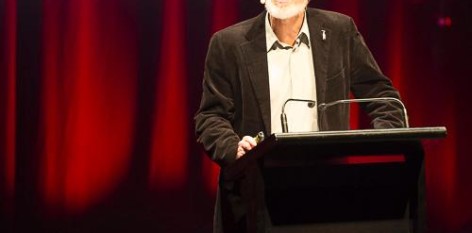

Sociologist and physician Nicholas Christakis (see his TED talks here) and political scientist James Fowler (see his TEDx talk here) agree that ideas don’t diffuse in human populations at random but through our networks. In their book, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives, they propose that our social networks affect every aspect of our daily lives, “exerting both subtle and dramatic influence over our choices, actions, thoughts, feelings, even our desires”.

Christakis and Fowler emphasise the importance of our specific location in that network, noting that the more central you are in your network, the more exposure you have to ideas spreading through it. In one study that tracked the happiness of around 5,000 people over two decades, the researchers used network visualisation software to demonstrate that happy people typically are located in the centre of their social networks within large clusters of other happy people.

3. The role of interpersonal connections

In his book The Diffusion of Innovations, first published back in 1962, sociologist Everett Rogers reviews how ideas or innovations spread across different fields. He synthesises research from over 500 studies on the spread of innovations in fields ranging from rural sociology to education, and discovers the importance of our interpersonal connections for spreading ideas.

Rogers explains that while mass media can introduce a new idea, most people depend on subjective evaluations from people they know and trust when deciding whether to adopt an idea or not. He cites a study done by Coleman, Katz, and Menzel among doctors in four communities in Illinois, which found that doctors who had more interpersonal connections opted to prescribe a new medication sooner than those who were not as interconnected. They concluded that the doctors’ decision-making was largely influenced by the personal experiences of their colleagues.

4. Network fluidity

Anthropologists Alex Bentley and Michael O’Brien and marketing guru Mark Earls agree that ideas spread through people but suggest that our networks aren’t quite so structured. In their book, I’ll Have What She’s Having: Mapping Social Behavior (named after the famous deli scene from the film When Harry Met Sally), they use computer models and real-life examples such as the swine flu public health scare to demonstrate how ideas spread through people copying what others do (more on this in an upcoming article).

Bentley, O’Brien, and Earls, however, caution against “the fashion for network analogies”, reminding us that the social landscape is dynamic with many of our social interactions and relationships in flux.

5. Network randomness

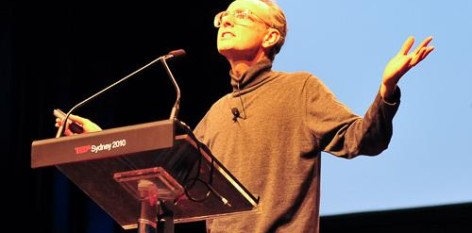

Physicist-turned-sociologist (and former Australian naval officer) Duncan Watts (see his TEDx talk here), studies networks by developing computer simulations and examining online diffusion in social media. Author of Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age, Watts has discovered that human networks are surprisingly unpredictable and quirky, arguing that trends can pick up steam in a network at random.

In one experiment, Watts and his colleagues found that when people were asked to rank new songs, those who were placed in “social influence” groups (where they could see which songs others had selected) conformed to the initial preferences of their fellow group members. This resulted in completely different top and bottom songs for each group, leading Watts to conclude that both random luck and merit play a role in spreading a trend.

What do you think? In the context of spreading ideas, does a social connection influence a trend, and if so, does the dynamic within these social networks make a difference? Is all this emphasis on network mapping overblown and just a theory du jour, or are we on the verge of discovering more about human interaction and how ideas spread?

Keep up to date with our latest news and join our TEDxSydney community here. It’s free to become a member and you will receive regular news and ideas. Watch out for our next piece on ideas ‘going viral’.

Original illustration for TEDxSydney by Rachel Peck