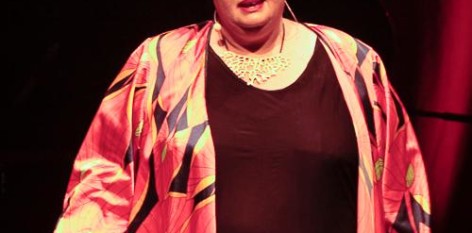

George Najarian, a jewellery maker and refugee, told me during the break at TEDxSydney Pitch Night that his father’s shop in Aleppo, Syria, had been completely destroyed. I had been to Syria in 2009 and remembered the beauty and community of the souks: arcades of shops created mini neighbourhoods where people traded goods, shared food and knew each other as families. For Najarian, the violence of war forced him to seek a better life. His message at Pitch Night? ‘Refugees are in a never-ending search for hope’, he said. ‘Hope to be happy again. This hope is you’.

‘We need friends, we need you’. Najarian’s pitch on the importance of friendship resonated with me as a newcomer to Sydney. It seemed to strike a chord with the multicultural audience as well and those who call Australia home.

‘How have you discovered friends here’? I asked George. ‘Through volunteer work’, he replied. ‘And meet-ups. By joining advisory boards of community organisations. And here at events like TEDxSydney’. It was indeed a gathering of minds at Pitch Night, and the upcoming TEDxSydney Salon on 30 October would be another chance to meet people and hear powerful views on how to solve today’s most pressing problems.

That night I learned a lot about what matters to Australians. I learned how, according to Owen Kelly, we might create an Australian version of the British ‘Grand Tour’ and ‘travel at the speed of nature’ across the land. Kelly proposed borrowing from the Slow Food movement and calling it ‘Slow Movement through Country’. I loved his idea and starting scheming about when I could plan my trip.

I learned that we can be creative in the face of corruption or injustice. Angry about the Australian bank crisis, Cris Parker argued passionately for a voluntary oath to be taken by banking and financial services in order to rebuild trust. It would be similar to the Hippocratic Oath taken by doctors, Parker explained.

Also borrowing from medicine, Ed Miller advocated for better employment numbers in Australia: ‘I want to imagine a world where we have a Medicare for jobs’, he said, after sharing a moving story about his father, an auctioneer. An economist himself, Miller appealed to logic: ‘No reasonable person can say that unemployment is a lack of character or skill’. He offered a new definition of work as ‘care for the land, care for each other and care for our elderly’.

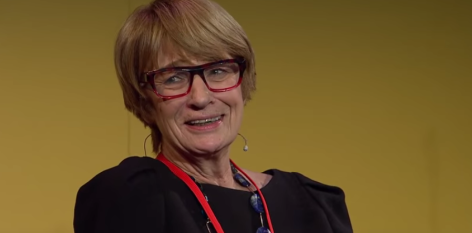

Tracy Brown spoke about Australia’s aging population and asked the audience a provocative question: ‘Whoever plans to get old’? Despite a few chuckles, everyone listened attentively, since aged care is of critical importance today. Brown suggested: ‘What if we monitor and map out health the way we do our finances?’ The result would bring dividends: ‘We’ll have peace at the end of our lives and we’ll no longer fear death. How would this change our midlife?’ Making it personal, and making it fresh, Brown asked, ‘How prepared are you for healthy aging?’ What a fantastic mindset, I thought, as I recalled my neighbour Helen, who at 92 has the most cheerful attitude toward aging of anyone I’d met. She welcomes each day with joy and monitors her health as carefully as her finances.

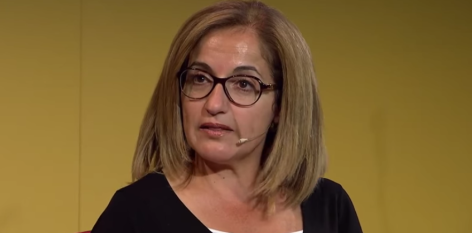

The concept of care for people in Australia shaped many pitches that night. Maggie Boutros talked about the language barriers in our health care system and how they negatively impact access and treatment. Her brilliant solution tapped into the promise of artificial intelligence: we can harness AI in order to translate medical procedures and documents into multiple languages. AI can give people control and consent in their own care.

Jessica Christiansen-Franks, a city planner who courageously pitched first, identified the obsession with big data in Australia and, indeed, across the world. Yet, she asserted, it’s ‘hard to find good data about what’s going on in neighbourhoods’. I reflected on her topic, neighbourhoods: those clusters of houses, shops, parks, apartment buildings.

I’ve experienced that here in Sydney people don’t just ask ‘What do you do?’ they ask, ‘Where do you live?’, meaning, of course, which neighbourhood? We map each other on a grid as we become acquaintances and friends. Christiansen-Franks ended her pitch with close attention to human data, in a manner that resembled a design-thinking customer-focused empathy methodology: ‘Imagine the problems we could solve if we understood the people living in those neighbourhoods’.

What about those marginalised by society? Remedying invisibility emerged as a powerful theme among the ideas pitched that evening. I learned from Melanie Tran that her identity as a woman—while often objectified and discriminated against—was ‘overpowered by disability’. Tran asserted that ‘being a woman with a disability brings on new challenges’ and she identified what she called ‘a national disgrace’ needing society’s attention.

Speaking about a different kind of invisibility, Sana Desai described growing up and taking a career as an engineer. For her, writing has become a creative outlet, and she launched Strategic Chaos to help balance her STEM brain with her need for artistic expression. Speaking about the life of the artist, Stephen Sewell asked if it ‘necessarily be one of suffering’? For Sewell—as for Desai, I think—there could be balance: ‘In overcoming but not living on pain’.

These pitches—and the future talks they might become—provided such a positive perspective on issues we all grapple with.

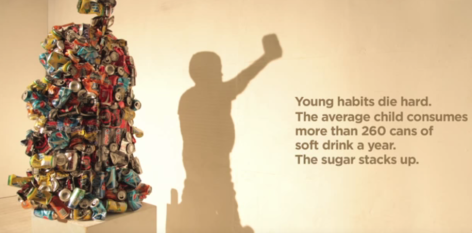

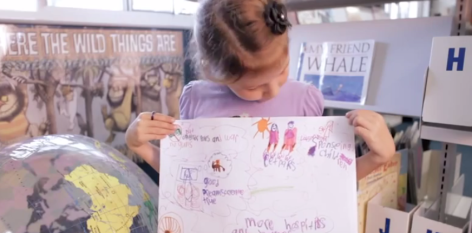

Andrew Weatherall, a pediatric anesthetist, introduced himself as ‘paid by the government to give drugs to children’. After the laughter subsided, he turned serious, describing the sheer terror that young children experience when facing an MRI machine. His idea? Promote wellbeing by making the exam ‘not just tolerable but enjoyable’. He would have kids themselves design the experience of medical care through the lens of their imaginations.

Advances in virtual and augmented reality can enable children to show us the landscape of their minds, Weatherall explained. We can give kids the power to set the rules and fashion the medical spaces they need to inhabit. He told us about an MRI machine turned into a space station and another one reconfigured as a pirate ship. During a break in the pitches I asked Weatherall about the age range of the kids, and he answered that he works with children as young as four. I thought of my nephews, who at three and five years old would build gigantic forts in their shared bedroom when they were supposed to be going to sleep, or who would race out clad in costumes for one last run around the house before being shuffled back to bed. Yes, ‘if kids could show us what is in their imagination’ we could transform the experience of medicine in Australia through artificial intelligence.

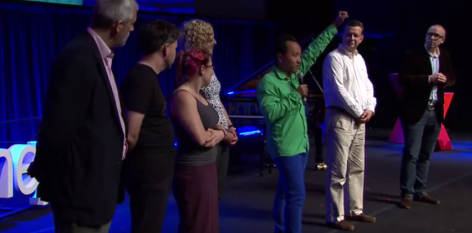

Hedayat Osyan, who won the Curator’s Grand Prize for Pitch Night, shared the harrowing story of his travels to Australia across many lands from Afghanistan to Indonesia to three months on Christmas Island. Once living and working in Australia, he soon discovered what he called ‘the dark side’ to the construction industry, which often exploited and ripped off refugee workers.

How, I wondered, is wellbeing of the individual—the lived experiences of each brave presenter on stage—wrapped up in the health of the nation? Conversely, what can the individual do to promote improvements in Australia?

Osyan, like so many of those pitching that night, had something to say, a vision to share. Within one year, Osyan turned himself from being a refugee dependent on Centrelink to an entrepreneur employing 15 people to assist refugees working in the construction industry. His own life, he told us, ‘is dedicated to contributing to Australian society’. By improving his life and the experience of others, he improves the nation. ‘What can’t you?’ he asked in the closing words of his pitch.

Why can’t we? Why can’t I? What I love about TED—and about these TEDxSydney ideas in particular—is that they allow for so many possible answers to those questions.

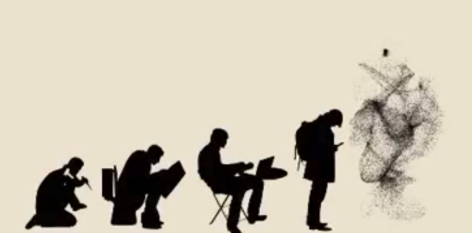

Bringing it home to our individual lives, Kaushik Ram, a neuroscientist, acknowledged and validated how very hard living in today’s world can be. ‘Everything happening around you is likely to change your heart’, he said, explaining that many neuro-diseases are caused by stress. Having just come from an appointment at the doctor earlier that day, I very much identified with the state he described. But then he offered a way to transform the mind and the body by reframing stress.

Perhaps that is how to move forward as a country: to reframe Australian struggles and problems into solvable situations. I think of Ram’s invitation for healthy living: ‘another good reason to go out dancing in the rain’. Turn neighbours into friends and bad experiences into positive realities. TEDxSydney Pitch Night lit a path for a better future, and the upcoming TEDx SydneySalon promises to keep the fire burning. In addition to attending, I have a new idea: to revisit the talks from the red carpet by watching TEDxSydney videos and learning even more about my new home.

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA – SEPTEMBER 2018: Pitch Night during TEDxSydney

The Sydney Opera House on September 25, 2018. (Photo by Jennifer Polixenni Brankin) @polixenn