Camera drones are, literally, inverting the way we see the world. But could it be they are also changing the way we feel about the world? Is there some link between our physical view and our emotional perspective? In other words, how does what we see have the potential to shape our emotional interpretation and view of the world?

Amongst the TEDxSydney 2016 film program is a short film that triggers such a conversation.

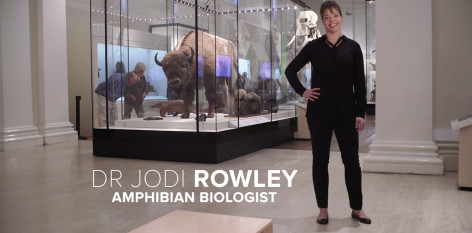

West Australian drone hobbyist and filmmaker, Jaimen Hudson, captured footage of what should have been the impossible; the extreme vulnerability of a lone paddleboarder who finds himself next to two magnificent southern right whales, some 150 metres from shore.

Yet rather than remain hidden in one man’s memory, this ultra-personal, once-in-a-lifetime experience was filmed and shared across news and social media channels world wide.

Headlines and viewers alike consistently described the footage in unusually emotive terms, declaring it “incredibly soothing” and that it “brings about inner peace”. Others found it “a great reminder of all life we need to preserve in the world”.

Why are millions of people so moved by seeing a man with some whales? Are they all pacifists and ocean environmentalists? Of course not. So what power lies within this drone footage to create such an emotional response en masse?

The key influencing elements are; perspective, and to a lesser extent, the absence of dialogue.

As is common with drone footage, there is no verbal narrative in Paddle Boarding with Whales. Without any dialogue to influence or distract the viewer, we are free to think or feel any way we like as the imagery unfolds.

This gap created by the unspoken frees us from the limitations of language and allows emotion to take reign. There is a shift from the intellectual to the sensory. The viewer is free to simply feel instead of think.

Although significant, the absence of dialogue does not, however, affect the viewer as much as the new visual experience the drone camera provides.

Humans, as a whole, are self-centric.

No matter how empathetic we consider ourselves to be, one can literally see the world from a single standpoint- our own. We can only see the world from this one perspective and the rest must be imagined. The ‘me’ and the ‘I’ is always at the centre of the what is doing the seeing, almost exclusively from eye height, give or take some 1.8 m from ground level.

But when we see the world from an aerial view, there is greater context. Our vision has been expanded, literally. We are no longer pinned to the Earth, confined to seeing our immediate environment from the ground up, with ‘me’ as the constant centre of everything we see.

This expanded vision with a wider context unconsciously and automatically tends to abolish, or diminish, our self-centric viewpoint. We can see that there is more- much more- than just our own tiny view world.

Quantum technological leaps, such as Google Maps satellite view, have gifted humankind with the ability to intimately see and explore our planet’s texture and terrain. Now we have flying cameras that grant us the ability to look back upon Earth from every possible height and angle.

Controlled by a tap on your phone (with the drone pilot safely positioned on terra firma), the size and dexterity of a drone camera delivers unprecedented access, and intimacy, to environments and situations that we never could have otherwise encountered.

As demonstrated in Paddle Boarding with Whales, the result is quite profound.

Viewers can behold these great, mysterious ocean dwellers, and man, side by side, with no barriers or machines between them. The light crystal blue waters enable the spectacle.

The drone camera allows us to gaze upon this breathtaking encounter from such heights and angles that were previously only known to birds or (depending on your beliefs) to God.

Our constant baseline of from which we measure, see and experience the world- the horizon- is no where to be seen.

Contemporary artist, writer, filmmaker and academic, Hito Steyerl, highlights the powerful significance the horizon has played over the centuries in her excellent article ‘In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective’;

“The horizon line was an extremely important element in navigation. It defined the limits of communication and understanding. Beyond the horizon, there was only muteness and silence. Within it, things could be made visible. But it could also be used for determining one’s own location and relation to one’s surroundings, destinations, or ambitions.”

Drone footage eliminates our relationship and dependance upon the horizon in a heartbeat.

Removed from our known viewpoint, we are cast into a floating state of suspension that is synonymous with dreaming, expansion and the freedom that comes with the sense of flying. Our self-centric perspective has been usurped to something greater than our known realm.

From this vastly new perspective, this footage of a man and two whales gives us a new way of not just seeing, but experiencing the world.

It quiets the mind and gives rise to something more experiential, almost serving as a mini-meditation.

This connection between a dramatic shift in visual perspective and expanded human awareness, is recognised most acutely in astronauts and cosmonauts after having viewed the Earth from space.

So said Canada’s first female astronaut, the remarkable Roberta Bondar who spent more than 8 days in space;

“To fly in space is to see the reality of Earth, alone. The experience changed my life and my attitude toward life itself.”

Similarly, renown cosmonaut and the first man to walk in space, Aleksi Leonov, said,

“The Earth was small, light blue, and so touchingly alone, our home that must be defended like a holy relic. The Earth was absolutely round. I believe I never knew what the word round meant until I saw Earth from space.”

And again, so said NASA Astronaut, James B. Irwin,

“That beautiful, warm, living object looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart. Seeing this has to change a man.”

Like fire, which can both give life and take it, drones that are crafted to seek and destroy have the potential to cause great harm to the world.

Yet perhaps as flying cameras, drones also offer us the very vision, wisdom, and empathy we need to save it.

Jaime Hudon’s film Paddle Boarding With Whales screens as part of the film program at TEDxSydney 2016.

Learn more about Jaimen’s unique and inspiring personal story.

Illustration for TEDxSydney by Calista Douglas.