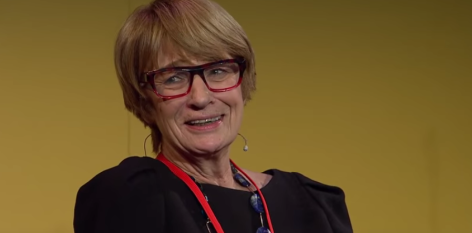

By the end of Thursday 21 May, 2015 the Post-it® Wall in the Northern Foyer of the Sydney Opera House was covered with questions, comments and insights from the attendees. A colourful and exciting wall of inspiration and collaboration! So, we gave the speakers an opportunity to respond to these questions and insights, thereby ‘closing the loop’ for the attendees. Here, Susan Butler – whose talk The Power Of The Dictionary was staged at TEDxSydney 2015– answers questions from the TEDxSydney community.

What is the longest word in the dictionary?

In the Macquarie Dictionary, for items of general vocabulary it is floccinaucinihilipilification. For encyclopedic entries, it is Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, a village in Wales. Of course the answer to this query varies, depending on the nature of the dictionary. There are some very long names of chemical compounds because they are arrived at by stringing all the different elements of the compound together.

What words have you taken out?

We rarely take words out of the dictionary although we may label them as Rare or Obsolete or part of someone else’s English. If a word has made its way into the dictionary at some point, it needs to be there just in case a reader is backtracking over an area of history or special interest, and encounters the word again. In these circumstances the reader is even more likely to need help with the meaning of the word, and they should be alerted to the fact that it is no longer in use.

Is the extinction of language greater than the development of new words?

The range of words that we all have at our disposal is pretty well constant. We use a few thousand words very commonly and up to about 7000 with reasonable frequency. After that our vocabulary follows our jobs, our pursuits, our interests, so it branches in different directions but we each travel along with about 20,000 words at our disposal.

If, however, you are thinking about the dictionary, then the online version just keeps collecting. We rarely lose words, so it would be fairer to say that the dictionary keeps expanding to cope with the new words rather than contracting.

How can we learn to adapt to language changes that are just so wrong?

The word that is the problem in this question is ‘wrong’. If you are having difficulty adopting a new word or usage because it doesn’t appeal to you, then you are very likely to lose the battle. The tide of usage will wash over you. But there are some generally agreed errors which careful users of English will continue to resist. Sometimes they win, sometimes they don’t. Having resisted for a couple of centuries the inclination to split the infinitive, the language community suddenly decided that that was a waste of time and that splitting the infinitive could be quite good fun. It didn’t really affect our comprehension of the meaning. However, there are other errors which really do create ambiguity and confusion and that we should resist. No one is obliged to give in to the ‘mistake’ of the language community if they don’t want to. You can fight on. Even if it is a losing battle, it will be a glorious one.

Can we design words?

It is harder than you think to create a successful new word. Some people are good at it. Lewis Carroll. Paracelsus. Blending two words is the commonest way but you have to produce a blend where the individual words are still discernible so that, while the word is new, the meaning is clear.

What ubiquitous words in internet culture do you predict will be added?

Who could have predicted the selfie or the emoticon or the meme? Last year it was lifehacking, greylisting, neknominate, watering hole attack and typosquatting. I await with interest what this year’s contributions will be.

Can you use the dictionary to create or influence positive social change?

Sadly no. We do no harm that I know of, but neither do we do good, except that, I think that if people have a respect for language, and that means a respect for the dictionary, then they will be more likely to be seekers after truth. But perhaps this is wishful thinking.

Any advice for an aspiring linguist? And how does one become a lexicographer?

There is so much complexity to the study of language, so many different facets to explore, and so many opportunities to enrich the lives of others. As for lexicography, in the past people have tended to learn it by doing it. There are some courses on lexicography available now and dictionary writing is a skill that is useful in a number of different contexts.

Are there changes to how we teach language and literacy that you would like to see?

I think that the general principles of the past still hold good – read widely, as David Malouf said just recently. ‘To be fully at home with the ideas and feelings that the language carries with it, we need to read as widely as we can.’ The best way to learn how to write is to do a lot of it, initially modelling our writing on writers that we admire, and slowly working our way towards our own voice. What has changed in recent times is the forms, the genres, the contexts in which we write. The basic skills are the same but they need to be reinterpreted for different times.

What inspired you to work with words?

Parents who loved reading and who were professional writers – journalists.

Do you have a favourite word?

Susurration. (It means ‘a whispering sound’ – the susurration of the casuarinas in the wind.)

Which words would you prefer NOT be in the dictionary?

Very long chemical compounds.

“A noble spirit embiggens the smallest man”. Why is a perfectly cromulent word like ‘embiggens’ not in the dictionary?

Because it is not a real word. People use it as a shared joking reference to the Simpsons. This does not make it a dictionary entry. When I can find people saying ‘Would you like to embiggen my helping of dessert, please?’ then I will put it in the dictionary.

What do you think of the borrowed usage from other languages that is not necessarily ‘correct’ in English language, such as ‘long time, no see’?

This becomes an idiom in English with its own English way of operating. It has great frequency so it presents no problem at all. It is a mistake to try to make a borrowed word or expression behave in English in exactly the same way as it behaves in the language from which it was borrowed. All borrowings adapt to their English context and take on a life of their own in their new language home.

Are you a grammar Nazi? And can we please add “Grammar Nazi” to the dictionary – they’re everywhere!

No I am not a grammar Nazi. At least, I don’t think I am. But then I hate it when people put ‘only’ in the wrong position in the sentence, and use ‘comprise of’ when they should say just ‘comprise’ or ‘consist of’. So maybe there is a bit of Nazi in me ….

We have a definition in the entry for Nazi that covers this kind of Nazi, but I will certainly add ‘grammar Nazi’ as an example.

There must be some linguistic habit or neologism that really annoys you?

We all pick up habits of speech which become so constant in our communications that they become irritating. I had to train myself to lose the habit of saying ‘Absolutely’. It is so much more convenient on radio to say ‘Absolutely’ than it is to say ‘Yes’. The former gives you that extra time to think what you are going to say next, and it has a certain flow to it. The latter gives you no time at all and is abrupt. But all good things have to come to an end. ‘Absolutely’ has been expunged from my lexicon I hope.

I am rarely annoyed by neologisms. I have a collector’s fascination with the next discovery, the next item to add to the collection.

At the end of TEDxSydney 2015, the Post-it® Wall in the Northern Foyer of the Sydney Opera House was covered with questions, insights and comments from the 17 extraordinary main stage speakers. Major Partner 3M Post-it® has compiled responses to the many questions posted on the wall by members of the TEDxSydney audience. They’re a fantastic read and provide previously unshared insights from speakers, building on their talks – you can read them all HERE.

Post-it® also took the opportunity to interview speakers on the day. Hear what Charlie Teo, Tom Uglow and Helen Durham have to say HERE